(And Exegetical Look at Luke 24:13-45)

INTRODUCTION

Jesus had been crucified. He was dead. Joseph of Arimathea had laid his beaten and lifeless body in a rock tomb. That was Friday. On Sunday, Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the Mother of James, and other women went to tend to Jesus’ body. But when they arrived at the tomb, Jesus was not there. Instead, they encountered two angels proclaiming that Jesus had risen—he was alive! The angels reminded the ladies of what Jesus had told them, saying, “Remember how he told you, while he was still in Galilee, that the Son of Man must be delivered into the hands of sinful men and be crucified and on the third day rise” (Luke 24:6b-7, ESV)1.

The women returned and reported these things to the eleven—Jesus’ closest disciples—and “to all the rest” (Luke 24:9b). But the most of the men thought these women were spinning wild stories and they chose not to believe them. Peter however, ran to the tomb and looked in, first seeing that the stone had been rolled away and then that the only contents remaining were the linen cloths that once wrapped Jesus’ body. He returned to the others and reported what he had seen. On the same day, two people (one unnamed and the other identified as Cleopas) were walking and discussing the various events concerning Jesus when a stranger appeared to them. As it turned out, they encountered the risen Lord on the road to Emmaus.

Volumes of been penned about the Emmaus encounter. Generations have dissected Luke’s account of Christ’s revelation of himself to these two witnesses. Some, it seems, have hunted for clues and codes beyond the most significant and obvious story, while others cannot even seem to accept that two people walking to a nearby town encountered the risen Jesus on the third day. Luke however, makes it very clear—Jesus is raised and he presented himself to these two witnesses on the road and in a home, as they were about to eat.

This post will closely examine the Emmaus road encounter as recorded in Luke 24:13-35. First, the passage will be summarized. Following the summation, and introduction of the author will be provided along with some background of the time and audience in which he was writing. Then the purpose of the book of Luke will be surveyed, and the context of the passage will be discussed. Once this foundation is laid, the content of Luke 24:13-35 will be the focus, starting with the most obvious message of the text: Jesus is alive! This and other aspects of the text will be offered by way of synthesis of the various ideas from the passage itself and commentaries on the passage. But this is not the ending point of the post. A practical application for today’s students of the Bible (the ultimate reason for study) will serve as the conclusion.

SUMMARY OF LUKE 24:13-16

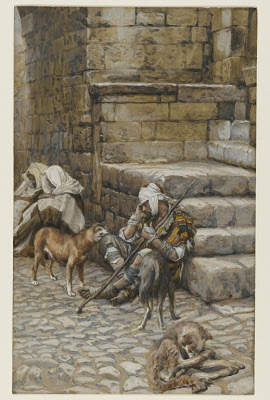

On the same day the women saw the angels, Cleopas and an unnamed person were walking from Jerusalem to Emmaus, which is about seven miles from Jerusalem. (13, 18). They were talking about all the things that had recently happened, that is, likely the things concerning Jesus, to include his mighty works and teaching, his trial, his crucifixion, the report from the women about their experience with the angels at the tomb, and the men who found the tomb empty (14, 19-24). They had hoped Jesus was the one to redeem Israel (21). Just then, Jesus came near, likely from the direction of Jerusalem, but the two travelers were kept from recognizing him (15-16). He asked the two people what they had been discussing and they stopped walking and were visibly sad (17). Cleopas then responded, as if in shock or just wanting to push away the stranger, asking Jesus if he were a visitor that had not heard anything about what had been going on in and around Jerusalem (18). Jesus replied, “What things?” and they told him about the many things regarding Jesus and the women and the empty tomb and that it was, on that day, the third day since Jesus died (19-24). Jesus responded, calling them “foolish ones” and “slow of heart to believe” the prophets (25). He then began explaining how all of the Scriptures were about himself (26-27).

As they approached Emmaus, it seemed that Jesus was continuing on, but the two people encouraged Jesus to stay with them. It was almost evening so Jesus went in to stay with them (28-29). Sitting at the table, Jesus took the bread, blessed it, broke it, and gave it to the other two (30). At that moment their eyes were open and they recognized Jesus; then he vanished (31). The two started talking about it and they realized that their hearts burned while they were talking with Jesus on the road as he opened up the Scriptures to them (32). Although it was getting dark, they returned to Jerusalem that same night and met with the eleven and the others gathered around. The eleven told the two, “The Lord has risen indeed, and has appeared to Simon!” (Luke 24:34). After this proclamation, the two reported what they had witnessed on the road and how they recognized Jesus as he was breaking the bread (33-35).

BACKGROUND

Who is the Author? According to Carson and Moo, “Most scholars agree that Luke and Acts were written by the same individual.”2 The strongest support comes from Theophilus, or rather, the author’s introduction to Theophilus found in both Luke 1:1-4 and Acts 1:1-2. Morris states, “Tradition unanimously affirms this author to be Luke.”3 While Morris, Carson, and Moo deal with the convincing proof that Luke is the author of the book that bares his name and its sequel, this post will agree with tradition for the sake of space.

Paul refers to Luke as a physician in his letter to the Colossians (4:14). Luke’s profession seems consistent with minor details of medical interest found throughout his writing. For example, when Luke discusses the fever of Peter’s mother-in-law, it is a “high fever” but Matthew and Mark only say it is a fever (Luke 4:38, Matthew 8:14, Mark 1:30). In addition, Luke appears to be a meticulous, detail-oriented man as he claimed to have “undertaken to compile a narrative” of the “eyewitnesses” and “followed all things closely for some time past” so that he could then “write an orderly account” for Theophilus in which Theophilus could have “certainty” concerning the things he had already been taught (Luke 1:1-4). While only speculation, it seems logical that this would require meeting eyewitnesses for interviews, likely reading anything else written about Jesus, listening to stories, and traveling to places where the events happened. Notes would likely be taken and organization would be necessary. And in fact, it is seen in portions of Acts that Luke was along with Paul and others on parts of Paul’s journeys.

In addition to his profession and likely mental capabilities, there is also a possibility that Luke was a Gentile Christian. This support comes from Colossians 4:10-14, where first Paul lists the names of those with him who were circumcised (Aristarchus, Mark, and Justus) and then lists others to include Luke. It can be assumed that, Luke, not being among the circumcised list, would be a Gentile. And being a companion of Paul, along with writing a positive book about Jesus in order to show Theophilus the truth of the things he had already learned, there is great cause to think that Luke believe the content of his two books and was a Christian. And for what it is worth, Foxe recorded in his Book of Martyrs that Luke was “hanged on an olive tree, by the idolatrous priest of Greece.”4

The Time and Audience. Just as much can be said about the scholarly work of the authorship of Luke, so too is the case of the date of its composition. Two strong hypotheses exist—one for authorship some time in the early 60’s and the other for a time between AD75-85.5 Either way, the time of authorship is sometime in the first century between 60 and 85, which is close enough in regard to the passage being examined in this post. Although the time of the passage itself takes place sometime between AD30 and 33, the most significant aspect of these dates is that many of the people identified in Luke would have still been alive at the time of its authorship. And as Luke set out to write a theological historical narrative of the accounts, his book would have been greatly challenged if it misrepresented the facts.

Luke lived in a mix of Jews and Gentiles and was likely writing for an audience of both. Carson and Moo speculate that even though Theophilus was the singular, primary audience, “it is almost certain that Luke had a wider reading public in view.”6 But given that Luke ties Jesus’ genealogy all the way back to Adam and assumes no Jewish tradition, it is likely that Luke was writing much more for the Gentiles than the Jews. In addition, much of Luke has a broader implication than just the Jewish people. And some of the cultural matters, such as including women in the narratives, suggest that Luke was writing from and to a culture other than the Jews. And if indeed Luke traveled with Paul, as this author believes, than it seems probably that Luke may have shared Paul’s desire to take the gospel to the Gentiles.

Purpose and Context. As already stated above, Luke’s purpose for his book was to provide and accurate account of the events of Jesus so Theophilus could have certainty in the things he was already taught. Considering the content of the book of Luke, it would seem that the things Theophilus was taught was likely the gospel of Jesus Christ and the way to salvation. The purpose of Chapter 24, of which the Emmaus road experience is a part, is to show that Christ has indeed risen and appeared to a variety of witnesses. It should be noted that of the three sections of this chapter (the angels’ declaration to the women, the Emmaus road experience, and Jesus’ appearance to the eleven and others) the Emmaus road event is the longest and vividly detailed.

The Emmaus road narrative is sandwiched between and account of the women, which the men did not believe, and Jesus’ climatic appearance to his group of disciples. In this context, the prospective of the two on the road serves as a bridge between the disbelief and the outright empirical testing of Christ’s resurrection. In the first panel (the story with the women), Jesus is not seen whatsoever. In the second, Jesus is seen but not recognized until the end. Here he must be heard and believed by faith more so than believed with the eyes. And finally, in the third panel, the disciples were able to touch and see Christ, and even witness him eat!

CONTENT

Jesus is Alive! As one reads Luke 24:13-35, it is easy to get sidetracked. Why were the two people restricted from recognizing Jesus? Was the breaking of the bread a communion service or just a meal, and why was Jesus serving it rather than the host? Where exactly did this event happen; can we pinpoint it on a map? Was the other witness Luke, or maybe Cleopas’ wife, or some other disciple? Why does Luke withhold the name of the second person? If the two disciples had not insisted on having Jesus stay, where would he have gone? Was Jesus presenting some kind of falsehood or lie by acting as if he was going on? All of these are interesting questions, but no other question from this text is worth anything if Luke’s most important and obvious point is not understood and accepted. The Lord is risen! Through the entire twenty-forth chapter, Luke is presenting accounts of Jesus’ resurrection, in detail, locations pointed out, witnesses named (mostly).

The Emmaus road account opens with two people discussing recent events, trying to make since of them. It is unknown why they were going to Emmaus, but it is possible that they lived there and were returning home from Passover as Culpepper and O’Day suggest.7 Regardless of their reason for travel, it is clear from verse 24 that these people were with the group that heard the account from the women. And they knew of Peter’s finding of an empty tomb; yet they did not remain in Jerusalem with the eleven and the rest of the disciples.

From the perspective of the two, a stranger came along side them. This stranger could see that they were carrying on a conversation and asked them about it. “The two disciples,” writes Geldenhuys, “would no doubt at first have felt offended at the obtrusiveness of the unknown Stranger, especially since they were talking so earnestly while they were walking and were so sorrowful and despondent.”8 But the stranger asks them another question; “What things?” he asks, showing that he genuinely is interested in the matter causing them such grief. And at this, these two confess their love of Jesus. They believed he was going to redeem Israel according to verse 21. Not knowing this man, they even take a risky position by placing blame for Jesus’ crucifixion on the Jews. To this Morris writes, “Notice that it is not the Romans but our chief priests and rulers who both delivered him up and crucified him. The reference to his being condemned to death implicates the Romans, but the chief blame is put squarely on the Jews.”9 They continue to express that this is not simply a matter of a prophet being put to death, but the one in which they had placed their hope.

A curious addition is the mention that this was the third day since Christ’s death. This would be of no value to the stranger unless they also told him what Jesus had taught and what the angles had reminded the women in verses 6-7: “that the Son of Man must be delivered into the hands of sinful men and be crucified and on the third day rise” (Luke 24:6b-7). It seems it must, at least at that moment, have been on the minds of these travelers. John Calvin argues, “For it is probable that he mentions the third day for no other reason that that the Lord had promised that after three days, he would rise again. When he afterwards relates that the women had not found the body, and that they had seen a vision of angels, and that what the women had said about the empty grave was likewise confirmed by the testimony of the men, the whole amounts to this, that Christ had risen. That the holy man, hesitating between faith and fear, employs what is adapted to nourish faith, and struggles against fear to the utmost of his power.”10

The stranger rebukes them for not trusting in what the Scriptures taught about the Messiah and the stranger begins to take them through the Law and Prophets showing them how these things were about him, about Jesus. As this was happening, the men experienced a burning within, according to verse 32, but this was still not enough for them to recognize Jesus. Verse 16 says, “But their eyes were kept from recognizing him” (Luke 24:16). Barclay argues that they were blinded and could not recognize Jesus because they were walking west toward the sunset and therefore blinded by the brilliance of the sun.11 While Barclay attempts to focus on the how, Morris simply points out, “On this occasion the implication appears to be that the disciples were somehow prevented from recognizing Jesus. It was in God’s providence that only later should they come to know who he was. Perhaps Luke wants us to gather, as Ford suggests, ‘that we cannot see the risen Christ, although he be walking with us, unless he wills to disclose himself’.”12 Once the three of them were inside and sharing bread, their eyes were opened and the recognized Jesus as their resurrected Lord. Duffield and Van Cleave see this scripture as pointing to the “uniqueness” of Christ’s resurrected body in that “it was not recognizable at times.”13 However, most commentators and theologians, even including Duffield and Van Cleave are in agreement with Driscoll and Breshears, who use verse 31, when the disciples’ eyes were opened to argue, “Jesus’ resurrected body was the same as his pre-resurrection body. His disciples recognized him as the same person who had been crucified.”14 The most important thing is not how or why the people on the road did not initially recognize Jesus, instead, it is that when they eventually did, Luke presents it as a proof of Jesus’ resurrection.

The reaction of the two disciples was so great that despite that evening was near, they absolutely had to go back to the eleven and others in Jerusalem and testify that Jesus has risen, he was alive and they had encountered him. Their conviction was overwhelming. This was not a specter or spirit they walked and talked with. It was not a vision that broke bread and gave it to them. It was the alive and physical Jesus. These two witnesses were excited to tell others and Luke used this event to convince his audience that Jesus was and is alive.

Jesus Revealed Himself. While the primary point of the passage, the most significant aspect that should be preached above all else, is that Jesus is risen, there are some other significant aspects of this passage worth investigation. The first is that Jesus revealed himself. The two people were walking together when Jesus came upon them. Verse 15 says he “drew near and went with them” (Luke 24:15b). He asked them the first question. He could have chosen not to reveal himself. He could have chosen not to ask them the first question. Instead, he not only chose to reveal himself to the two travelers, he chose to use them as witnesses to others.

The Reaction of the Witnesses. The next point worth a brief mention is the reaction of the two people once they recognized Jesus. Jesus had just handed them bread and this in some way helped them recognize him (Luke 24:35). But then he vanished. At that moment, the two quickly reflected on their encounter with him on the road; however, they did not remain in discussion about the past for very long. That very hour, they went back to their friends to testify that they had encountered Jesus. This was an event that must be shared. And just as they had shared what they understood about Christ with a man they believed was a stranger, their initial reaction was to share their experiences and encounters with this stranger.

Who Were These Witnesses? Luke names one of the witnesses, Cleopas, lending more credibility to the account as Culpepper an O’Day point out.15 Many commentators have offered different speculation as to the identities of the unidentified traveling companion in route to Emmaus. Some, including Morris, say the unnamed person was Luke because the detail is so vivid.16 Another suggestion is that the other traveler is the wife of Cleopas. Still another idea from liberal arguments is that the particular witness no longer would testify that he saw the risen Christ so Luke left him unnamed. However, if this were the case, why would Luke include the account at all? There is the possibility that these two where the two disciples mentioned in Mark 16:12-13, but in that account, the rest did not believe the two disciples. How could these be the same accounts with such a discrepancy? In any case, it is significant to see that Cleopas is mentioned nowhere else in the Bible. The other person is not even named. These two are likely regular people; and although there is no solid indication of such, most commentators address them both as men. In light of the larger point, it might be best to let the unnamed disciple remain unidentified as Luke intended.

Breaking the Bread. Some commentators, especially of much older publications, cast a light of communion upon the breaking of bread in this text. This author believes Morris best addresses this aspect of the text, writing,

Bread was commonly broken at the prayer of thanksgiving before a meal. Some have seen here a reference to the breaking of bread in the communion service, but this seems far-fetched. It would have been a very curious communion service, broken off in the opening action and as far as we can see never completed. And it would have been quite out of place. In any case the two were not present at the Last Supper (cf. 22:14; Mark 14:17) so they could not have recalled Jesus’ actions then.17

However, there may have been something significant about the breaking of bread or it may have simply been the timing because Luke 24:35 says, “Then they told what had happened on the road, and how he was know to them in the breaking of the bread.”18 There is also the possibility that the disciples were present at another meal with Jesus or that something else unique to Jesus—maybe a mannerism—had something to do with their eyes being opened. However, this author is inclined to think that it was in the teaching of Jesus, which may have culminated at that moment, to a point where faith came through hearing.

APPLICATION FOR TODAY

While there is much to examine in this vivid text, it is important that the primary point Luke presents is addressed. Without seeing this point, the other points will offer nothing of value. Christ revealed himself to two travelers on the road after he had been crucified and buried. It was on the third day, just as he had promised. Jesus is alive, indeed!

As present day readers examine this passage of Luke 24, they, like the travelers, are faced with the decision to examine both the Old and New Testament Scriptures, see the accounts of Jesus, and answer the question, Is he the Savior? Readers must ask themselves if they believe if Jesus is risen? Are the accounts of the witnesses true? The travelers on the road were contemplating the testimony of the women and the report that Peter found the tomb empty. As they were contemplating, Jesus met them on the road. While it may not be that Jesus will physically manifest himself to those contemplating Christ, he does meet us where we are to reveal himself to us. He opens our eyes. The remaining question then, is will we believe; and if so, will we share our encounters with Jesus with others?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Calvin, John. Calvin's Commentaries. Harmony of the Evangelists, Matthew, Mark and Luke.

Vol. XVII. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Books, 2009.

Carson, D. A., and Douglas J. Moo. An Introduction to the New Testament. Grand Rapids,

Michigan: Zondervan, 2005.

Crossway Bibles. ESV Study Bible: English Standard Version. Wheaton, Ill: Crossway Bibles,

2008.

Culpepper, R. Alan, and Gail R. O'Day. The New Interpreter's Bible. The Gospel of Luke, the

Gospel of John. Volume IX. Nashville, Tenn: Abingdon, 1995.

Driscoll, Mark, and Gerry Breshears. Doctrine: What Christians Should Believe. Wheaton, Ill:

Crossway, 2010.

Duffield, Guy P., and Nathaniel M. Van Cleave. Foundations of Pentecostal Theology. Los

Angles, Calif: Foursquare Media, 2008.

Foxe, John. Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Edited by William Byron. Accordance 9.1.1. OakTree

Software, Inc, Version 1.4.

Geldenhuys, Norval. The New International Commentary on the New Testament. The Gospel of

Luke. Grand Rapids (Mich.): W.B. Eerdmans, 1979.

Morris, Leon. Luke. Nottingham, England: Inter-Varsity Press, 2008.

___