INTRODUCTION

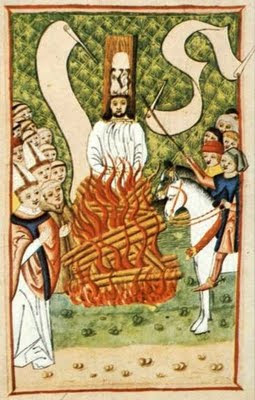

Among modern evangelicals, interest in the Protestant Reformation seems to tie many preachers and writers together. It is as if referencing Calvin or Luther nearly grants some kind of mystical weight to any point. Works by Calvin and Luther, and books about them, fill pastors’ and professors’ shelves. Occasionally Zwingli is remembered but not often; Balthasar Hubmaier on the other hand, is a forgotten theologian, despite the reality that his theology is closer to that of most evangelicals today. Where Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli remained magisterial, finding it impossible to separate the Church from the State, Hubmaier believed that separation is necessary for the free will of the believer and the establishment of the free church. The Lord’s Supper remained a theological difficulty for the popular reformers—not so with Hubmaier. Luther and Calvin stood firm on the matter of paedobaptism while Hubmaier understood that the Bible teaches that baptism is for believers only and that the Church is an institution of baptized believers. He was—despite disagreement with Zwingli, Luther, and Calvin—baptized by immersion, a belief and action that eventually cost him his physical life. Hubmaier was formally educated, trained under Johann Eck, and published a substantial amount of theological material. Although once a Catholic priest in the Rosensburg Cathedral, Waldshut in Breisgau, and in Schaffhausen, he eventually rejected much of his Catholic theology, joining with the Anabaptist movement and marring Elisabeth Hügeline.1 Hubmaier was imprisoned and tortured under Zwingli’s orders, and on March 10, 1528, burned at the stake.2 Elisabeth was drowned a few days later.3“Some people,” writes Wenger, “compared his death with that of Jan Hus in 1415.”4

Balthasar Hubmaier’s life and theological work is a significant but often overlooked contribution to the Church as evangelical Christians understand it today. While it cannot be said that without Hubmaier’s work the free church of Baptist and many other denominations would not be, it can and will be argued in this post that Hubmaier was a significant and radical reformer who should not be overlooked, but remembered, read, and understood for his brave and faithful contribution to not only the Reformation, but the evangelical Church. This post will first examine the setting of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries in which Hubmaier lived. Then the scope will narrow to his life and theology, followed by an investigation of Hubmaier’s contribution to the Protestant Reformation and the Church today.

BACKGROUND OF THE PERIOD

“As the fifteenth century came to a close,” writes González, “it was clear that the church was in need of profound reformation, and that many longed for it. The decline and corruption of the papacy was well known.”5 The late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, through religious, political, social, and educational circumstances were ripe for reformation. While it might have shocked the world to read Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses, it should have been because Luther was brave enough to say it, not because it came unexpectedly. If it had not been Luther, it surely would have been another. “[The Reformation] was not so much a trail blazed by Luther’s lonely comet, with other lesser luminaries in its train, ” argues D. F. Wright, “as the appearance over two or three decades of a whole constellation of varied color and brightness, Luther no doubt the most sparkling among them, but not all shining solely with his borrowed light.” The under girding of the Reformation was the humanist reformers. González argues, “Long before the Protestant Reformation broke out, there was a large network of humanists who carried the vast correspondence among themselves, and who hoped that their work would result in the reformation of the church.”6 In today’s terms, a humanist might be thought of as one who places or worships humanity over deity, often called a secular humanist;7 but the humanist of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were quite different. “In this context,” states González, “the term ‘humanist’ does not refer primarily to those who value human nature above all else, but rather to those who devote themselves to the ‘humanities,’ seeking to restore the literary glories of antiquity. The humanists of the sixteenth century differed greatly among themselves, but all agreed in their love for classical letters.”8 Often called the “Prince of Humanists,” Erasmus of Rotterdam is considered the godfather of the movement and its leader.9 Wright calls Erasmus the “morning star” of the constellation of the Reformation; further writing, “for most Reformers were trained humanists, skilled in the ancient languages, grounded in biblical and patristic sources, and enlightened by his pioneer printing of the Greek NT of 1516.”10

As education swung in the direction of humanism, studies in the biblical languages gained a foothold, and Catholic priests were being educated at the highest levels, it became difficult for some to overlook the abuses, corruption, and troubled theology of the Catholic Church. Luther sounded the alarm when he struck hammer to nail on the door at Wittenberg in 1517, and many others joined him in what started as an effort to reform the Church. However, reformation was not to be and eventually schisms began. Although not the first to separate from Rome, Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli became the front men of the Reformation, climbing up to the shoulders of their predecessors such as the Waldensians, Wycliffe, Lollardy, and Hus to look and then go beyond where those before them had attempted to venture. Meanwhile, the Pope fought back. Entire geographic regions shifted from Catholic to Lutheran to Catholic to Calvinist and so on, the various nation states of Switzerland being the most unstable. The social and economic climates were tossed in the storm of theological shifts church-state relations. In this setting, those in disagreement with one another were branded heretics and burned at the stake. Wars were fought over which religious group or leader would have control of the various European states.

Throughout Europe, ideas started surfacing that questioned the practice that one would be a member of a church, and therefore a citizen of the state, simply by birth into it.11 Luther and Calvin sided with Rome on this matter, as did Zwingli, eventually. Others, hoping to be more obedient to Scripture saw it differently. “The church must not be confused with the rest of society,” writes González in explaining the minority opposing position.12 “Their essential difference is that, while one belongs to a society by the mere fact of being born into it, and through no decision on one’s own part, one cannot belong to the true church without a personal decision that effect.”13 This in and of itself was seen as a treasonous act against the state. González continues, “In consequence, infant baptism must be rejected, for it takes for granted that one becomes a Christian by being born in a supposedly Christian society. This obscures the need for a personal decision that stands at the very heart of the Christian faith.”14

The ideas of various disconnected radical reformers found a public voice in a group of students studying under Zwingli in Zurich. Calling themselves “The Brethren,” through careful reading and study of Scripture, decided that the reformation had not gone far enough. Members of this group, according to Lichty, “were highly educated young men, students at the universities or sometimes priests. The influence of humanist learning was strong among them, as was seen especially among the circle of Conrad Grebel in Zurich. Like Erasmus, they taught freedom of the will and were relatively optimistic about the possibilities of human betterment.”15 They were all recipients of infant baptism and believed that credo baptism was the only baptism taught in the Bible and obedience was necessary for the Church. Zwingli, their teacher and now a religious and political leader disagreed. So on January 21, 1525 in the public square in Zurich, Conrad Grabel baptized George Blaurock. Then Blaurock baptized several others, forming a congregation or a church of adults baptized as believers. Those baptized as adults were branded “Anabaptists,” meaning “rebaptizers.” They were quickly seen as subversive to the state for their radical theological views and therefore persecuted, often killed by drowning as symbolic irony.16 “All the initial leaders [of the Brethren], with the exception of Wilhelm Reublin,” records Estep, “were dead within five years. Zürch lost its three major Anabaptist leaders in short order. Grabel died of the plague in 1526. Felix Mantz became the first ‘Protestant’ to die at the hands of Protestants in 1527, and George Blaurock was burned at the stake in 1529. The suppression of Anabaptism in Switzerland almost completely exterminated the movement.”17 It is in this volatile time that we find Balthasar Hubmaier, joined by confession and believer’s baptism with the Brethren in Zurich.

THE LIFE OF HUBMAIER

Early Life as a Roman Catholic. Hubmaier was born in approximately 1480 or 1481, and he grew up in Friedberg, Germany,18 On occasion, he was known as Dr. Freidberg, presumably after his hometown or the University of Freidberg.19His upbringing was modest and Moore speculates that his basic education was in Friedberg; but then tentatively wanting to enter the priesthood, he likely went to the cathedral Latin school in Augsburg six miles to the West. He matriculated at the University of Freiburg in Breisgau in 1503. 20 “So advanced was Balthasar in his studies” writes Moore, “that he received the bachelor of arts degree after his first year at the university.”21 He continued to study theology under Dr. Johann Eck, although Hubmaier considered entering the field of medicine. Eck would soon there after “become the flaming defender of Catholic orthodoxy against the Lutheran reformation.”22 Also interesting to note is that not only was Hubmaier Eck’s favorite student, he was also a couple years older than his teacher.23

In 1507, Hubmaier was forced to take a job as a schoolteacher in Schaffhausen, Switzerland for financial reasons. However, as Moore quotes Eck, “he returned to his accustomed studies, which were under my guidance.”24 Once back to his studies, Hubmaier mastered Latin and studied Greek and Hebrew. He also studied with Johann Faber who would eventually persecute Hubmaier. After his ordination, he occasionally preached and served as a priest. When Eck left for the University of Ingolstadt in 1510, Hubmaier replaced him as rector.25 Packull reports that in Eck’s absence, “Hubmaier seemed to be involved in the defamation campaign against Eck's detractors. Along with Urbanus Rhegius, Hubmaier became one of Eck's1most controversial students.”26 Eighteen months later, Hubmaier followed Eck to Ingolstadt where he earned a Doctorate of Theology, upon which he was made a professor and given a preaching position in the city’s largest church. In 1516, Hubmaier took employment as a cathedral preacher in Regensburg.27

In Regensburg, Hubmaier lead a campaign against the Jews living in the city; however, the Jews had the protection of Emperor Maximilian I and Hubmaier was somewhat unsuccessful until the Emperor’s death. After hearing of the death, Hubmaier and the town residents continued and amplified their campaign, leading to the eviction of the Jews and the destruction of their synagogue. “In the tearing down of the synagogue,” writes Moore, “a master stonemason was injured, fatally, it appeared. A few hours later he revived, and the people said it was a miracle of the virgin Mary—manifesting her glory in the very place where she had been dishonored by the Jews. On the site of the demolished synagogue a Catholic chapel was erected and, at Hubmaier’s suggestion, named Beauteous Mary (zur schönen Maria).”28 This chapel not only became the responsibility of Hubmaier, it became a destination of a pilgrimage movement and was remodeled into a larger church building. In 1519, a papal bull granted 100 days off from purgatory for the visitors of Beauteous Mary and the place became a mad house of activity and miracle claims. Hubmaier sought duties elsewhere.29

Eventually, Hubmaier was offered a position as chief priest in Waldshut, a small Austrian town on the border of Hapsburg. “For about two years, 1521-1522, Hubmaier served as a model priest in Waldshut,” according to Moore.30 “He celebrated mass, preached effectively, presided in ceremonies and processions, even introduced new celebrations. As always, he sought to work in harmony with state and church authority.”31 However, he grew bored and reached out to the humanist Johann Aldephi, the town physician in the nearby Schaffhausen, Switzerland, as well as, Christian humanists Beatus Rhenanus, Johannes, Johannes Oecolampadius, and Wolfgang Rychard. As Zurich began undergoing reformation, Hubmaier also had regular correspondence with Desiderius Erasmus, Heinrich Glarean, and Konrad Pelikan. It was here that he engaged in detailed studies of the letters to the Corinthians and Romans. He also took visits to Freiburg and Ulm where he compared old and new ideas about church life. Maybe out of loneliness or boredom, he returned to Beauteous Mary as a chaplain but retained his position in Waldshut.32 However, returning to Beauteous Mary, all the excitement over proclamations of miracles caused Hubmaier a conflict of conscience. “His thinking had begun to take new directions,” writes Moore. “He was still quite uncertain, however, just where it would all lead.”33 Hubmaier felt uncomfortable dealing with the miracle claims, and although it would have been good for the Beauteous Mary’s visitor traffic, he could not publicize them. Moore writes, “Within a few weeks of taking up the work again in Rogensburg, he experienced what might fairly be called his most basic conversion. He became an evangelical.”34

The Transition. Although never claiming Lutheranism for himself, his beautiful; revelation of faith came as he was quietly meeting with a group of Lutherans in Rogensburg. Almost eminently he returned to Waldshut were he could study and explore his new convictions. “Hubmaier still had many questions in his mind,” states Moore, “but on thing he was firm: he theology, when worked out, must come from the Bible.”35 However, due to the changed nature of his preaching, his bishop filed a complaint about him. Hubmaier initiated contact, started establishing relationships with the Swiss reformers in the Zurich canton, and started making trips to reformation friendly towns. He preached to large crowds in churches and in open-air settings and he lead Bible studies. And he met with Zwingli in Zurich.36

It is difficult identify day or time when Hubmaier parted from his Catholic roots and sided with the Reformation in Switzerland; however, it seems that at least theologically, that day was already behind him by the time he had met with Zwingli the first time. Zwingli and Hubmaier spoke a few times, discussing a wide range of topics. On the topic of baptism, Moore writes, “They both agreed that the New Testament gave no real support for the practice of infant baptism and Zwingli said, Hubmaier reported later, that children should not be baptized until they had been instructed in the faith.”37 Later, and in the public spotlight, Zwingli reversed his position and Hubmaier was critical of him arguing, “You used to hold the same ideas, wrote and preached them from the pulpit openly; many hundreds of people have heard it from your mouth. But now all who say this of you are called liars. Yes, you say boldly that no such ideas have ever entered your mind and you go beyond that, things of which I will hold my tongue just now.”38 However, before the split between Hubmaier and Zwingli, Hubmaier was invited to the Second Zurich Disputation in October of 1523. Hubmaier spoke at the disputation and was clearly seen as a Zwinglian.39 It was here the Hubmaier argued, “For in all divisive questions and controversies only Scripture, canonized and sanctified by God himself should and must be the judge, no one else: or heaven and earth much fall (Matt. 24:35). [...] No the judgments of God can only be known out of the divine Word, as Scripture truly testifies to us. [...] For holy Scripture alone is the true light and lantern through which all human argument, darkness, and objections can be recognized.”40 Already, Hubmaier understood baptism to be for believers only and a symbolic act rather than a sacrament; and he, like Luther, stood firmly on Sola Scriptura.

Returning to Waldshut, Hubmaier’s separation only continued. Potter writes, “Waldshut, however, was no part of the Swiss Confederation; it was Catholic city ruled for Charles V by Ferdinand of Austria. A Catholic ruler must root out heresy or be in danger of excommunication.”41 Word got back to the various authorities and Hubmaier and his Waldshut were investigated and branded “Lutherans.” It was 1524. Earlier that year, Hubmaier published his Eighteen Thesis, which clearly demonstrate a separation from Catholic theology and Hubmaier wrote to his friends in Ratisbon, according to Potter, “that he had no intention of returning to his duties [in Waldshut]: he was now no longer an orthodox Roman Catholic.”42Based on the Eighteen Thesis, Hubmaier held strongly to Sola Fide, preaching in the language of the people, and open access to the Bible; and he rejected purgatory, the mass, pilgrimages, devotion to images, and forced celibacy. “Truth Is Unkillable!” he boldly declared.43 Ferdinand demanded the suppression of the Lutheran teaching—instead, the city stood by Hubmaier, declared its independence, and removed all Catholic priests from the city. Shortly there after, the Peasants’ war began in the nearby Black Forrest.44 It was also in this year that distance grew between Zwingli and Hubmaier, and by the end of 1524, Hubmaier had sided with Grabel against Zwingli and his beliefs. Hubmaier was officially and Anabaptist.

New Life and the Worldly Troubles it Brought. With the publication of his Eighteen Theses, Hubmaier started a post-Catholic publishing career the dwarfed the sum of all the other early Anabaptist leaders combined. However, his writing and preaching placed his believes in plain view, bringing persecution upon him and his parish. Due to political and Catholic pressure, Hubmaier sought and found refuge in Schaffhausen. While the canton of Schaffhausen was not his defender, they also took a position of tolerance and let him be, despite numerous requests that Hubmaier be handed over to the Austrian authorities or the Catholic Church.46 It was here (or on his way here) that Hubmaier wrote he Theses Against Eck. Dr. Eck, Hubmaier’s former teacher, according to Moore, “was not perhaps Germany’s leading theological defender of popes and ecclesiastical custom. He had written bitter denunciations of reformers in Germany and Switzerland and once or twice the name of Hubmaier appears in his attacks.”47 This document consisted of 26 theological statements with Scriptural references, leaving absolutely no mistaking where Hubmaier’s theology had landed.

The political climate was growing red-hot. A few of Hubmaier’s letters have been published, but what may be his most famous work, On Heretics and Those Who Burn Them, ignited a flame and eventually Waldshut came under Catholic attack. Zurich unofficially sent by way of a band of armed citizens.48 On Heretics and Those Who Burn Them is a statement of 36 articles in favor of the free will of belief and an attack against those who burn those with opposing views. Article 1 opens with the delectation, “Heretics are those who wantonly resist the Holy Scripture,” and concludes with, “Now it appears to anyone, even to a blind person, that the law [which provides] for burning of heretics is an invention of the devil. Truth is Unkillable.”49 The argument between these two bookends used Scripture throughout, once again demonstrating his strong reliance upon and reverence for the truth of Scripture. The political and military pressure against Hubmaier ebbed and flowed for a while, at times being fierce, at other times Hubmaier preached to Swiss soldiers after Waldshut peaceably opened their gates to them.50 Both the Catholic and Zwingli’s men hunted Hubmaier. During this time, a small band of men formed the first Anabaptist congregation and were expelled from Zurich. Also in this time, Hubmaier grew more vocal and declared his view that children should not be baptized and that both baptism and the Lord’s Supper should be conducted biblically.51 He renounced the idea that Catholic priests were an intermediary between man and God and should remain celibate. On January 13, 1525, he married Elsbeth Hugline. A week before Easter, Wilhem Reublin baptized sixty people—Hubmaier was among them. The following day, Hubmaier baptized many others, and through the Easter season, he claimed to have baptized 300 people.53

After Waldshut fell to the Catholics, Hubmaier, weekend by illness, escaped into the country but was eventually captured by Zwingli. For four months, he was detained in the Zurich city hall, still sick and frail. Zwingli had given an execution order for many Anabaptist which included Grebel, Mantz, Blaurock, Aberli, and Hubmaier.54 Archduke Ferdinand requested to extradite Hubmaier, causing Hubmaier to believe the only way he would survive, even if he remained in the Zurich jail, was to recant. In his infirmity, he wrote a statement of recantation; however, it was not enough for the local authorities. They desired that publicly read his recantation in the churches of Zurich in an effort to humiliate the Anabaptists. The first church was to be the Fraumunster. Moore tells the story,

After Zwingli had preached, Hubmaier was called upon to read his recantation. Just before the service, it seems, he had learned about imperial representatives being in the city. He evidently decided that Zurich now intended to turn him over to the Austrians and that no recantation would save him. He hurriedly wrote down some notes on a scrap of paper for his own sincere defense of the freedom of faith. Later he said this was intended for the use in his defense before the Austrians in case he were handed over to them. A surge of moral strength welled up within him, however, as he rose to read the recantation. He sued the hastily scribbled notes rather than the carefully worded recantation in making his statement to the congregation.55

Hubmaier bodily stated that he would not and could not recant and then proceeded to defend his belief of adult baptism. He was immediately carted off to jail where he was tortured until he stated that the devil inspired his statements and that his fellow Anabaptists were heretics.

For three more months, Hubmaier was kept in a wet cell in what was called the Water Tower. Poor treatment and torture were continued as punishment. Somehow, Hubmaier managed to write a short confession called the Twelve Articles of the Christian Faith, which was published the subsequent year. He also wrote a number of other short works from the Wellenberg prison. At the same time, Grebel, Mantz, Blaurock, and other Anabaptist were being held in a new prison named the Heretics Tower. With Zwingli’s blessing, the local authorities issued an order that anyone known to have rebaptized another person would be killed by drowning. Grebel, Mantz, and Blaurock were sentenced to life in prison; however, shortly after sentencing the entire group escaped. Hubmaier, not having been with the others, again offered to recant. Wanting to use this against the Anabaptist, Hubmaier was again transported to three churches were he read his insecure statement of recantation. Knowing his statement was a ruse, Zwingli and the authorities placed Hubmaier under heavy guard. Somehow, he was still able to escape and he and his wife made their way to Constance. Some time later, he left for Moravia. All the while, he continued to write and from Moravia published a substantial amount of work for such a short period.56

Dying for His Beliefs. Hubmaier’s time in Moravia allowed him the opportunity to work though and publish his theological ideas. While he was likely considered among the Swiss Brethren, some of his work put a wedge between himself and the others, mainly, his position on against pacifism outlined in Concerning the Sword. However, this time for writing, preaching, and reflection would end when Archduke Ferdinand was crowned king of Bohemia in 1527, just three years after Hubmaier’s baptism. Ferdinand appointed Johann Faber, Hubmaier’s former fellow student and friend, as the persecutor of heretics. The Hubmaiers were taken under custody on a charge of insurrection. The couple was taken to the Kreuzenstein Castle and the charge of heresy was added. By the end of that year, Faber began days of hearing. Fearful of the results of his previous interrogations and charges, Hubmaier was careful how he responded, at first holding true to his beliefs but constructing his statements in less than controversial ways. Eventually he had to take his stand on Scripture, offering a negative statement on purgatory and the intercession of the saints. Neither did his lack of support for any Catholic tenants did not help his case. But none of that would matter given the wide and bold scope of his writing. Hubmaier pleaded for the opportunity to support his positions with Scripture before an open council but his requests never reached Ferdinand. When ordered to write a statement of recantation, he instead wrote a confession of guilt to aiding the peasants at Waldshut. He also included his confession of beliefs but in no way called them heretical. His statement was read publicly and Faber had them published. On March 10, 1528, “without complaint, courageous at the end,” Balthasar Hubmaier was burned at the stake.57 Three days later, Elsbeth Hubmaier had a stone tied to her and she was thrown into the Danube River.58

Dean Stephanus Sprugel of the University of Vienna recorded that on the stake, Hubmaier cried out, “O gracious God, in this my great torment, forgive my sins. O Father, I give you thanks that you will today take me out of this vale of tears. I desire to die rejoicing, and come to you. O Lamb, O Lamb, take away the sins of the world. O God, into your hands I commit my spirit.”59 Again, only this time in Latin, he declared, “O Lord, into your hands I commit my spirit.”60 He shouted to the onlookers, “O dear brothers and sisters, if I have injured anyone, in word or deed, may they forgive me for the sake of my merciful God. I forgive all those who have harmed me.”61 Before the smoke overtook him, Hubmaier’s last words were, “O Jesus, Jesus!”62

HUBMAIER’S THEOLOGY

After reading much of Hubmaier’s work, it is clear that most evangelicals and all Baptists are closely connected to the theology held by the Anabaptist theologian. His writing could easily be picked up today and look like a theological survey of the modern evangelical church. For example, in answering the question, “‘What, or how much at least, must I know if I desire to be baptized?’” Hubmaier responds, “This, and this much, you must know from the Word of God before you let yourself be baptized: That you confess yourself a miserable sinner and guilty, that you also believe the forgiveness of your sins through Jesus Christ, and that give yourself into a new life with the firm resolution to improve your life and to order it according to the will of Christ, in the power of God the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit.”63 Although many Anabaptists were killed for this belief, this is not much of a stretch for evangelical churches today. In fact, A Form for Water Baptism outlines a set of questions that should be asked of a potential recipient of baptism. It is essentially a multi-question form of the Apostles’ Creed followed by a personal question of confession. This form could be used today without any realization that Hubmaier penned it in 1527.

In the simplest of summation, Hubmaier agreed with Luther in that salvation comes by faith alone and Scripture alone is the final authority: Sola Fide and Sola Scriptura. They agreed that Scripture should be taught and read in the language of the people and the common person should have access to the Word of God for himself or herself. Hubmaier rejected the authority of the pope, and elevation of the priest between God and man, mandatory celibacy, the intersession of the saints, and purgatory—to include the penitence works—pilgrimages, relics, festivals, and indulgences. This however, is where the agreement with Luther ended. Hubmaier came to understand the Lord’s Supper as an instructed symbolic memorial act and a communion of the believers rather than a sacrament that somehow brought about salvation. And that is where he left Calvin and Zwingli. Hubmaier further believed that the Church is made up of believers only, who upon credo baptism find entry. Therefore, he rejected infant baptism, meaning he also rejected the union of church and state as it existed in his day. Man is gifted with an aspect of free will, according to Hubmaier, belief and consentience cannot be forced. That being said, man cannot hold the title of Christian simply by being born to Christian parents in a Christian geographical area. This is where agreement between Hubmaier and the Brethren end. Unlike the Brethren and the stream of theology that came be rest on the Anabaptist movement, Hubmaier was not a pacifist. His work, On the Sword laid out a biblical position away from pacifism, and because of this, many modern Anabaptists do not claim Hubmaier as a theological forefather. And finally, this is where Hubmaier and modern evangelicals end. The doctrine held by Hubmaier that is rejected by evangelicals today was his view of Mary. Hubmaier held that Mary remained the “perpetually pure and chaste Virgin.”64

Much can be discussed about Hubmaier’s theology, except his ideas will appear as common place because they are so close to those of orthodox evangelical Christianity today. However, Hubmaier was among the minority in his day. He was seen as a heretic and even died at the hands of other Protestants for views recognized as common today. But this does not mean that his theology should be neglected. Every evangelical student of the Bible should have the complete works of Balthasar Hubmaier on the shelf next to his or her other systematic theology books.65 Understanding the theology of Hubmaier is extremely insightful in understanding the roots of many theological doctrines today.

HUBMAIER’S CONTRIBUTION TO THE REFORMATION

Balthasar did not ring the bell of Reformation as Martin Luther did in Wittenberg. He has not gained the popularity of John Calvin. And Hubmaier was not a lone, superstar reformer like the three most revered—Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli. So one might ask what his contribution to the Reformation was. In short, Hubmaier was the theologian and writer of the radical reformation stream, the stream that came to be known as the Anabaptists. On Hubmaier, Friedmann writes,

It is clear that besides Balthasar Hubmaier (d. 1528), who was a doctor of theology (from a Catholic university), there were no trained theologians in the broad array of Anabaptist writers and witnesses. Hubmaier was a special type, greatly esteemed by Christian radicals by not really emulated and followed after. Many of his theological ideas crept into Anabaptist thinking, such as, for instance, his doctrine of the freedom of will, or his teaching concerning the two ordinances of baptism and the Lord’s Supper.66

More significantly, the Anabaptist theology—with the exception of pacifism—gave birth to the idea that the church must be free of governmental control and manipulation, is comprised of believers only through baptism by confession, and that the Lord’s Supper is not a sacramental guarantee of God’s grace. With Hubmaier at the beginning, the idea that magisterial church-government leadership is not the biblical picture for the Church. Each person has the free will to believe how he or she will; therefore, the government cannot force belief or membership into any specific church. If it is not obvious, Hubmaier’s contribution to the Reformation was the significant second part of Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli’s work. Had it not been for the Anabaptists, there is a possibility that the Church today would look much like the Catholic church of the sixteenth century, only baring the name of Luther or Calvin. If not for Hubmaier, the ideas may not have been work through so thoroughly, and they certainly would not have been published and preserved for the Church today. Today’s evangelical church has much for which to thank Hubmaier.

CONCLUSION

While Balthasar Hubmaier is not as popular as other Reformers, he is as significant, if not more so. As a protestant killed at the hands of other protestants, martyred for his faith, his is an fascinating part of Christian Church history. Today, evangelicals stand upon his shoulders and see higher and farther, whether they realize it or not. And they stand more in line, more united, with his theological contribution than any other Reformer. Therefore, it is important that Hubmaier not be forgotten, that his books not become merely dust on a lonely shelf of empty libraries. It is the hope of this blogger, that this post has generated a greater interest in Hubmaier and his work so that the reader will seek out additional works about Hubmaier as well as his original writing.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Elwell, Walter A. Evangelical Dictionary of Theology. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2001.

Estep, William R. Anabaptist Beginnings (1523-1533): A Source Book. Nieuwkoop: B. de Graaf, 1976.

Friedmann, Robert. The Theology of Anabaptism; An Interpretation. Studies in Anabaptist and Mennonite history, no. 15. Scottdale, Pa: Herald Press, 1973.

González, Justo L. The Story of Christianity: Reformation to the Present Day. San Francisco, Calf: Harper & Row, 1984.

Hindson, Edward E., and Ergun Mehmet Caner. The Popular Encyclopedia of Apologetics. Eugene, Ore: Harvest House Publishers, 2008.

Hubmaier, Balthasar, H. Wayne Pipkin, and John Howard Yoder. Balthasar Hubmaier, Theologian of Anabaptism. Classics of the radical Reformation, 5. Scottdale, Pa: Herald Press, 1989.

Moore, John Allen. Anabaptist Portraits. Scottdale, Pa: Herald Press, 1984.

Packull, Werner O. "Balthasar Hubmaier's gift to John Eck, July 18, 1516." Mennonite Quarterly Review 63, no. 4: 428-432. 1989. ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials, EBSCOhost (accessed September 7, 2010).

Potter, G. R. "Anabaptist Extraordinary Balthasar Hubmaier, 1480-1528." History Today 26, no. 6 (June 1976): 377-384. MasterFILE Premier, EBSCOhost (accessed September 5, 2010).

Verduin, Leonard. The Reformers and Their Stepchildren. The Dissent and Nonconformity Series, 14. Paris, Ark: Baptist Standard Bearer, Inc, 2000.