John and the Holy Spirit

/The Fourth Gospel, that is, the Gospel of John, is often viewed in light of the author’s stated purpose of documenting specific signs “so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name.”[1] In addition, this Gospel is often viewed as providing great evidence of the hypostatic union of Jesus’ simultaneous deity and humanity. And Carson and Moo argue, “The elements of what came to be called the doctrine of the Trinity find their clearest articulation, within the New Testament, in the Gospel of John.”[2] However, while the Fourth Gospel’s main focus appears to be on Jesus, the Gospel also demonstrates the person, purpose, and deity of the third member of the Trinity, the Holy Spirit.

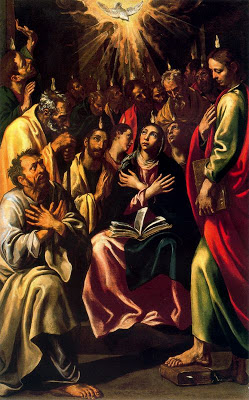

John, the son of Zebedee, walked with Jesus and was his disciple for the duration of Jesus’ earthly ministry. The Synoptic Gospels often record that John was among Jesus’ inner-circle of disciples, regularly present for many special events as an eyewitness. And if John, the son of Zebedee, is the beloved disciple and author of the Fourth Gospel (as this author believes he is), there is clear evidence through the Gospel of John that John had a special relationship with Jesus. In addition, John was present in the upper room at Pentecost when the Holy Spirit came upon the small group.[3] And the remainder of the New Testament provides an indication that John experienced many aspects of the faith, being animated and moved by the Holy Spirit, which greatly aided him in his calling as an Apostle to teach the world. This post will examine one aspect of his teaching—the Holy Spirit. First, a discussion of many sections of the Gospel of John and one unique word choice will be offered. Next, this post will examine (and speculate) what John may have understood during the time of his narrative compared to what he understood at the point of authoring his Gospel. Then, before the conclusion, this post will look at what aspects of the Holy Spirit would be unknown without the Fourth Gospel.

When attempting to understand what the beloved disciple’s Gospel teaches on the Holy Spirit, it is best to look at the evidence from John’s hand. John uses two words when referring to the Holy Spirit. The first is pneuma, which is the more common use for the Spirit throughout John, as well as throughout the New Testament. Fifteen times this word is used in reference to the Holy Spirit in John’s Gospel. Eight times John’s Gospel uses pneuma in reference to the nonphysical part of a person or a person’s soul, and once it is in reference to wind. Looking to John’s other canonical writings, pneuma twice refers to breath, twice to a mood or intention, 12 times to demonic or angelic beings, and 20 times it is used in reference to the Holy Spirit. There are 319 uses of the same word outside the Johannine corpus, all being employed much in the same way as John’s usages. And considering that Klein Bloomberg and Hubbard argue, “[The Septuagint (LXX)] became the Bible of most of the early Christians during the writing of the NT,” there is a possibility that John knew the Hebrew Bible by way of the Septuagint (LXX); therefore, it may be worth noting that pneuma appears 350 times in the Septuagint (LXX).[4] The second word John uses in reference to the Holy Spirit is parakleōtos. This word is used significantly less, only by John, and will be discussed in greater detail below. Attention will now shift to specific passages in John where either one of these two words is used in reference to the Holy Spirit.

The Spirit on Jesus: 1:32-33. John the Baptist, the man who baptized Jesus in the Jordan river, declared that he did not know who the Lamb of God would be, but that God told him he would know when he saw the Spirit descend and remain on him. In addition, John said of Jesus, “I saw the Spirit descent from heaven like a dove, and it remained on him.”[5] The Spirit served as an anointing sign to the Baptist. And through John the Baptist’s witness, John, the Gospel author, is able to provide a sign of Jesus’ anointing for his soon-coming ministry. “The descent of the Spirit on Jesus,” states Bruce, “marked him out as the Davidic ruler of Isa. 11:2ff, of whom it is written, ‘the Spirit of the Lord shall rest upon him’, as the Servant of whom God says in introducing him in Isa. 42:1, ‘I have put my Spirit upon him’, and as the prophet who announces in Isa. 61:1, ‘The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord as anointed me . . .’”[6]

Baptizing with the Spirit: 1:33. John the Baptist was baptizing with water, but the one who sent him to baptize reviled that another would be coming with a greater baptism. This baptism is different than anything the Baptist could offer, and in fact could only be given by the Son of God. Carson suggests that this Baptism in (or with) the Holy Spirit points forward to a new age when God will pour out the Spirit onto (or into) his people, alluding to Ezekiel 36:25-26 where following a water cleansing, God implants within the person a new heart and a new spirit.[7]

Born of the Spirit: 3:5-8. Jesus introduces and interesting concept to Nicodemus, a Pharisee. He tells Nicodemus that he must be born again and that rebirth is of water and Spirit. Morris suggests a couple meanings of this passage. The first is that the water represents a repentance baptism, such as John the Baptist was administering; and the Spirit is, “namely the totally new divine life that Jesus would impart.”[8] The second meaning of being born of water and Spirit could suggest that being born of water points to a natural birth and then being born of the Spirit is a birth of spiritual regeneration. Either way, Jesus is clear that one must be born of the Holy Spirit in order to enter the kingdom of God, meaning that the Holy Spirit holds a significant role in this second birth and man’s ability to enter the kingdom of God.

Given without measure: 3:34. Fulfilling Isaiah’s prophetic words in Isaiah 11:2, 42:1, and 61:1, the Holy Spirit rests upon the Servant. Therefore, the Holy Spirit is suggested as having an empowering quality. Jamieson suggests that while some human-inspired teachers might have the Holy Spirit to some degree, God has bestowed the Holy Spirit upon Jesus in an unlimited measure.[9]

Giver of life: John 6:63. In this passage, Jesus gives credit to the Spirit as the giver of life. The Fourth Gospel has already shared the words of Jesus stating that the Holy Spirit plays a significant role in the new birth. Now he confirms that it is the Holy Spirit that gives life. Carson claims, “One of the clearest characteristics of the Spirit in the Old Testament is the giving of life.”[10] However, in this verse the Spirit as the giver of life is being sharply contrasted against the flesh. And in the very next sentence, Jesus says that it is the words that he speaks that are spirit and life. If it is in Jesus’ words that life and spirit are discovered, than there is a connection between the Spirit and the words of Jesus. To this idea, Morris suggests,

A woodenly literal, flesh-dominated manner of looking at Jesus’ words will not yield the correct interpretation. That is granted only to the spiritual man, the Spirit-dominated man. Such words cannot be comprehended by the fleshy, whose horizon is bound by this earth and its outlook. Only as the life-giving Spirit informs him may a man understand these words.[11]Receive the Holy Spirit: 7:39; 20:22. At the Feast of Booths, Jesus declared that for anyone who believes in him, “Out of his heart will flow rivers of living water.”[12] John writes that this statement is in reference to the Spirit, “whom those who believed in him were to receive, for as yet the Spirit had not been given, because Jesus was not yet glorified.”[13] Marsh states, “This is written not only from the perspective of this particular narrative of the gospel, but also from the later perspective of the Church, in which every believer has received the Spirit (at baptism).”[14] The Spirit was not yet present in the form that Jesus was stating, but at a point after Jesus’ ascension, man would be in a position to receive the Holy Spirit. The Greek word behind the translation of receive, is lambanō, which means, “to take.”[15] There is an implication of some level of choice or action of willingness involved. Recorded in John 20:22, Jesus breathes on the disciples and commands them to “Receive the Holy Spirit.”

Spirit of Truth who dwells in you: 14:15-17. It is here for the first time that parakleōtos is used in reference to the Holy Spirit. Jesus is about do depart and he is preparing his disciples for the time when he is gone. But Jesus is not leaving them alone and without a helper or champion; he will ask the Father to send the Holy Spirit, the parakleōtos. But while this coming Helper will dwell among men just as Jesus did, he will also dwell within the disciples. Jesus also declares, “In that day you will know that I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you.”[16] John, it seems, has painted a picture of an amazing union between the Holy Trinity and the believer.

The Teacher: 14:25-26. Jesus has been with the disciples for some time, teaching and training them. He has taught them many things, and soon it will be their responsibility to teach others. However, it seems that at times, the disciples failed to understand what Jesus was attempting to teach them. Understanding did not come until after they received the Holy Spirit (see John 2:22 and 12:26, among many passages contained in the Synoptic Gospels.) But in this text, Jesus promises them a teacher who will “teach [them] all things and bring to [their] remembrance all that [Jesus had] said to [them].”[17] Bruce points out, “Now they are told that when the Paraclete comes, he will enable them to recall and understand when Jesus taught: he will serve them, in other words, as remembrancer and interpreter.”[18]

The Person and Witness: 15:26. There are two significant aspects about the Spirit in verse 26. First, as time moves forward, the Spirit will serve as a witness to testify about Jesus. Here, as elsewhere, the Spirit is given a purpose. (Subsequently, the disciples are also called upon the testify about what happened while they walked with Jesus.) Second, John says, “he will bare witness about me.”[19] Carson argues that it is no accident; John intentionally used the word ekeinos.[20] The Greek word, ekeinos, is a masculine pronoun and Carson demonstrates that its use is inconsistent with the “(formally) neuter status of the preceding relative pronoun.”[21] John is referring to the Holy Spirit in personal, male terms. He is thinking of the Holy Spirit as a person! Incidentally, John uses ekeinos for the Holy Spirit again in John 16:13-14.

The Guide who only speaks what he hears: 16:13-14. This passage specifically demonstrates that the Holy Spirit is not operating by his own authority, but is declaring what he hears, which glorifies Jesus. Theologically, this is one of many demonstrations of the Trinity’s simultaneous unity and equality of being in perfect submission to one another in the service of their unique purposes. “The Holy Spirit never magnifies Himself,” writes Duffield and Van Cleave, “nor the human vessel through whom He operates. He came to magnify the person and ministry of Jesus Christ. Whenever He is truly having His way, Christ, and none other, is exalted.”[22]

Parakleōtos: 14:16, 14:26, 15:26, 16:7. In addition to the summary of passages above, there is some value in looking at a special term only John uses for the Holy Spirit. The use of parakleōtos is found only five times in the New Testament—four times in the Gospel of John and once in First John (John 14:16, 26; 15:26; 16:7; 1 John 2:1). Incidentally, it makes no appearance in the Septuagint (LXX). Köstenberger states “The translation of this term has proved particularly difficult, since there does not seem to be an exact equivalent in the English language.”[23]

English Bible translations each seem to handle the parakleōtos differently. For example, the English Standard Version (ESV) uses the word “Helper” in all of the Gospel uses and “Advocate” in John’s first Epistle. The American Standard Version (ASV) uses “Comforter” in the Gospel use and “Advocate” in the letter. The Holman Christian Standard Bible (HCSB) uses “Counselor” in the Gospel, and once again, “Advocate” is used in First John; and the same is true for the King James Version (KJV). The New International Version (NIV) also selected “Counselor” in the Gospel and simply says “one” in the Epistle. “Helper” is the choice for the New American Standard Bible (NASB) except in the letter, where “Advocate” is the selected word. The New English Translation (NET) uses “Advocate” for every occurrence, as does the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) and the New Living Translation (NLT).

Turning to dictionaries and lexicon a variety of meanings for parakleōtos are presented. Perschbacher defines it as, “one called or sent for to assist another; an advocate, one who pleads the cause of another, [. . .] one present to render various beneficial service, and thus, the Paraclete, whose influence and operation were to compensate for the departure of Christ himself.”[24] Strong defines it as, “counselor, intercessor, helper, one who encourages and comforts; in the NT it refers exclusively to the Holy Spirit and to Jesus Christ.”[25]

As mentioned above, there are clear indications in the Fourth Gospel that suggest that while John was with Jesus during his earthly ministry, there were many things John did not fully understand. John 2:22 states, “When therefore he was raised from the dead, his disciples remembered that he had said this, and they believed the Scripture and the word that Jesus had spoken.” John 12:16 echoes this same idea. Both of these texts offer strong support for the development of John’s theology, and John 14:25-26 leaves the reader with the impression that the Holy Spirit likely had a profound impact upon John’s understanding sometime after the Pentecost. While it would only serve as speculation to attempt to determine what John learned from Jesus and what he learned from the Holy Spirit, a survey of John’s teaching on the Spirit can be juxtaposed against the Old Testament to determine how much John could have learned from Scripture. And what John teaches that has no counterpart in the Old Testament can then be assumed to have been taught to John either by Jesus or the Holy Spirit.

Before an examination of John’s teaching is contrasted against the Old Testament, it should be noted that there is still a possibility that John was unaware of a specific scriptural teachings on the Holy Spirit; and in fact, it was still Jesus or the Holy Spirit that served to teach John about these things. However, by conducting this examination, it can at least be determined what knowledge might have been available to John prior to encountering Jesus and the Holy Spirit.

John’s knowledge from the Scriptures. Staring with the Spirit being upon Jesus as an anointing power, John may have understood the idea of empowerment of the Spirit upon a person by examples from David and Saul, such as the example in First Samuel 16:13. And he may have understood the idea of the Holy Spirit coming upon the Servant of God as Isaiah’s prophecies dictated (Isaiah 11:2, 42:1, 59:21, and 61:1). However as far as the Spirit dwelling within the believer, the Old Testament showed the Spirit coming on someone for a time to empower him, but there is no indication of the Holy Spirit actually dwelling within a person.

As for a baptism of the Spirit, this concept is only alluded to in Ezekiel 36:25-26; but even with this allusion, it likely would have been difficult to formulate a solid understanding of the Holy Spirit’s role in the cleansing and regeneration of the heart. Joel 2:28 provides a picture of a pouring out of the God’s Spirit that leads to an empowerment, but this picture of empowerment is lacking in the regeneration suggested in Ezekiel. Without encountering Jesus or the Holy Spirit, it is unlikely John would understand the baptism of the Spirit as he writes about it in the first chapter of his Gospel. And if baptism of the Spirit was a difficult concept without Jesus or the Holy Spirit’s teaching, being born of the Spirit would have been even more so. Not even Nicodemus, an educated Pharisee understood what Jesus was teaching at the time.

As John came to understand that the Spirit is in some way the giver of life, his thoughts were likely contrasted against passages that declare that God is the giver of life (like Genesis 2:7 and Psalm 80:18, for example). But in reading these passages, one would probably not concluded that that the Holy Spirit is the giver of eternal life as Jesus was teaching. And John would not likely be alone in this lack of understanding because John’s sixth chapter of his Gospel shows many disciples turning away from following Jesus due to confusion of Jesus’ statements about the life found in the Spirit and the lack of life in the flesh.

Psalm 25:8-9 and Isaiah 54:13 are examples of God being the teacher and instructor to his people. It may have been difficult to understand this teacher as being the Holy Spirit, but it certainly would not be a stretch to know that God does want to teach and remind his people of his ways. In fact, Jeremiah 31:33-34 suggests that God would eventually write his law upon the hearts of the people.

The Fourth Gospel provides some unique contributions to the believer’s understanding of the Holy Spirit. Without John’s Gospel, we would not have the discourse with Nicodemus, which includes a unique picture of being born of water and the Spirit as a requirement to enter the kingdom of God. John is also the only one to use the term parakleōtos, offering a different understanding of the Holy Spirit. Yes, John does use this word once in First John, but that use has legal cogitations, where as the other four uses suggest that the Spirit is a helper, counselor, and assisting presence. John’s use of ekeinos clearly demonstrates that the Holy Spirit is a person and not a thing or force. This is the most articulate argument for the personage of the Holy Spirit; without John, the other arguments may not have led the Church to the same conclusion. And John makes it clear that the Holy Spirit came because of Jesus’ death and glorification. He is present because Jesus has ascended to the right hand of the Father.

While John demonstrates the humanity and deity of Jesus, he also teaches a great deal on the Holy Spirit. After reviewing the ten passages of Scripture and reviewing John’s unique reference for the Holy Spirit, it should be clear that John held a strong understanding of the purpose and function of the Holy Spirit. Some of these characteristics of the Holy Spirit are found only in the Fourth Gospel, and given his understanding of the many aspects of Holy Spirit (some demonstrated only by John), the Fourth Gospel should be viewed as a valuable source for teaching on the Holy Spirit. It is the hope and prayer of this author that the readers of this post will be compelled to examine John’s articulation of the Holy Spirit for themselves, so that they will develop a stronger understanding of John’s written demonstration of the person, purpose, and power of the Holy Spirit.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bruce, F. F. The Gospel of John. Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 1994.

Carson, D. A. The Gospel According to John. Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 1991.

Carson, D. A., and Douglas J. Moo. An Introduction to the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Mich: Zondervan, 2005.

Duffield, Guy P., and Nathaniel M. Van Cleave. Foundations of Pentecostal Theology. Los Angles, Cali: Foursquare Media, 2008.

Jamieson, Robert, A. R. Fausset, and David Brown. Commentary Critical and Explanatory on the Whole Bible. OakTree Software, Inc., 1871. Version 2.4. [Acccessed by Accordance Bible Software 9.2.1, March 6, 2011.]

Klein, William W., Craig Blomberg, and Robert L. Hubbard. Introduction to Biblical Interpretation. Nashville, Tenn: Thomas Nelson, 2003.

Köstenberger, Andreas J. Encountering John: The Gospel in Historical, Literary, and Theological Perspective. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2002.

Marsh, John. Saint John. Philadelphia, Penn: Westminster Press, 1977.

Morris, Leon. The Gospel According to John. Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 1984.

Perschbacher, Wesley J. The New Analytical Greek Lexicon. Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson, 1990.

Strong, James, John R. Kohlenberger, James A. Swanson, and James Strong. The Strongest Strong's Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Grand Rapids, Mich: Zondervan, 2001.

1. John 20:31, English Standard Version (ESV). Unless otherwise noted, all quotes from the Bible will be taken from the ESV.

2. D. A. Carson and Douglas J. Moo, An Introduction to the New Testament, (Grand Rapids, Mich: Zondervan, 2005), 278.

3. Acts 1:13ff.

4. William W. Klein, Craig Blomberg, and Robert L. Hubbard, Introduction to Biblical Interpretation (Nashville, Tenn: Thomas Nelson, 2003), 253.

5. John 1:23b.

6. F. F. Bruce, The Gospel of John (Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 1994), 53-54.

7. D. A. Carson, The Gospel According to John (Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans, 1991), 152.

8. Leon Morris, The Gospel According to John (Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans 1984), 216.

9. Robert Jamieson, A. R. Fausset, and David Brown, Commentary Critical and Explanatory on the Whole Bible (OakTree Software, Inc., 1871 Version 2.4.) [Acccessed by Accordance Bible Software 9.2.1, March 6, 2011.]

10. Carson, The Gospel According to John, 301.

11. Morris, 385.

12. John 7:38b.

13. John 7:39b.

14. John Marsh, Saint John (Philadelphia, Penn: Westminster Press, 1977), 344.

15. James Strong, John R. Kohlenberger, James A. Swanson, and James Strong (The Strongest Strong's Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible. Grand Rapids, Mich: Zondervan, 2001), 2986.

16. John 14:20.

17. John 14:26.

18. Bruce, 305.

19. John 15:26

20. Carson, The Gospel According to John, 529.

21. Ibid.

22. Guy P. Duffield, and Nathaniel M. Van Cleave, Foundations of Pentecostal Theology (Los Angles, Cali: Foursquare Media, 2008), 295.

23. Andreas J. Köstenberger, Encountering John: The Gospel in Historical, Literary, and Theological Perspective (Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Academic, 2002), 157.

24. Wesley J. Perschbacher, The New Analytical Greek Lexicon (Peabody, Mass: Hendrickson, 1990), 308.

25. Strong, 3884.

* "Ausgießung des Hl. Geistes" pictured in this post is in the public domain.

** This post was, in its entirety or in part, originally written in seminary in partial fulfillment of a M.Div. It may have been redacted or modified for this website.