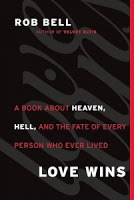

Love Wins by Rob Bell (Chapter 4)

/

[This review is a review in parts. If you are just joining this review, start with "Love Wins by Rob Bell (Prolegomena)."]

At this point, I have two confessions. First, I put the book down after Chapter Three for a while. I was feeling frustrated that I set out on this journey through Bell's book. Second, I have now completed the book, having read the remaining chapters during a flight across the country. This is not to say that the review from this point forward will not capture my thoughts and impressions as I was reading each chapter. I've been taking notes and recording my thoughts in the margins and in the bizarre spaces between each paragraph that make the book seem as if were intended to be one long blog post rather than a bound book. I guess now I'm thankful for the abnormal formatting.

The title of Chapter Four asks, "Does God Get What God Wants?"

But first, Bell opens the chapter with jabs at doctrinal statements found on other church websites. It is clear that he is in disagreement with their approach of sharing their beliefs on what he feels should be a welcoming, seeker-friendly website. (Interestingly, while Bell defends his own ideas saying, "[Christian faith] is a deep, wide, diverse, stream that's been flowing for thousands of years, carrying a staggering variety of voices, perspectives, and experiences" (x-xi), he seems for forget to leave room for these other churches. Is the stream only so wide and so diverse that other churches are only accepted if their ideas are flowing the way Rob Bell wants? It does seem so.

Chapter Four is about universalism, and thus far, if any chapter has demonstrated that Bell has beliefs in the universalism camp, it's this one. (I realize that outside of the book, Bell has been declaring that he is not a universalist, but there are aspects of this chapter that would argue otherwise.) Here, Bell discusses universalism--that is, his views of universalism, specifically two views. The first is that heaven is "a universal hugfest where everybody eventually ends up around the heavenly campfire singing 'Kumbaya,' with Jesus playing guitar" (105). Through jabbing questions, he implies that this is incorrect and nobody would want this anyway. The second view is that a person has rejected God so much so that he or she is no longer human; thus all humans go to heaven but all non-humans do not. But this implies that there are people that are not human and that kind of implies an us verses them. Then he argues that these are long standing and traditional views starting with the early Christian church (107). But while Bell argues against these views (or I should say, he asks loaded questions of them), he conveniently never takes a position for himself. He doesn't ever seem to suggest a correct answer; he only questions the ideas for which which he doesn't care for or agree. And in the way he questions, he seems to takes a stand against these views, much like his approach to the other Christian's websites.

Back to the question of the chapter title: "Does God Get What God Wants?" The bulk of this chapter--and I might argue much of the books thus far--hinges on a verse in First Timothy 2. Bell quotes it as, "God wants all people to be saved and come to a knowledge of the truth" (97). The passage itself comes from First Timothy 2:3-4 and this translation looks very similar to the NIV version. The ESV translates the verses as, "This is good, and it is pleasing in the sight of God our Savior, who desires all people to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth" (1 Timothy 2:3-4, ESV). Bell's argument goes like this: If God wants something and doesn't get it, he's not powerful and therefore not a good God. However, Bell argues, God does indeed get everything he wants and therefore everybody WILL be saved and have a knowledge of the truth. . . eventually. And if Bell's way of thinking about this is not correct, according to his own argument, then God must be a failure.

To support his understanding of this specific Scripture, Bell looks at some other verses (citing only the chapters from where they come). First he looks at Isaiah 45, Malachi 2, Acts 17, and Romans 11, to argue "What we have in common--regardless of our tribe, language, customs, beliefs, or religion--outweighs our differences. This is why God wants 'all people to be saved'" (99). Then using other Scripture, Bell works to show his readers that the Bible says everybody will be saved. Many of the Scriptures are interpreted with questionable methods. Here's the list of Scriptures Bell uses to support his unrealistic view that everybody will be saved. I highly recommend you turn to each of these chapters and read them yourself, in their entirety.

Psalm 65 -- "all people will come" to God (99)

Ezekiel 36 -- "The nations will know that I am the Lord" (99)

Isaiah 52 -- "All the ends of the earth will see the salvation of our God" (99)

Zephaniah 3 -- "Then I will purify the lips of the peoples, that all of them may call on the name of the Lord and serve him shoulder to shoulder"

Philippians 2 -- "Every knee should bow . . . and every tongue acknowledge that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father." (99)

Psalm 22 -- "All the ends of the earth will remember and turn to the Lord, and all the families of the nations will bow down before him." (100)

Psalm 22 -- "All the rich of the earth will beast and worship; all who do down to the dust will kneel before him--" (100)

Shifting to the idea that God does not fail, Rob uses Psalm 22 to say, "So everybody who dies will kneel before God, and 'future generations will be told about the Lord. They will proclaim his righteousness, declaring to a people yet unborn: He has done it!'" (100). Following this passage, Bell again says that God does not fail and it is this idea that the prophets were affirming. They turned to this theme again and again (100). To support this claim, Bell turns to more chapters. Again, I suggest these chapters be read in their entirety.

Job 23 -- "Who can oppose God? He does whatever he pleases" (100)

Job 42 -- "I know that you can do all things; no purpose of yours can be thwarted" (100)

Isaiah 46 and 25 -- "Surely the arm of the Lord is not too short to save nor his ear too dull to hear?" (101)

Jeremiah 32 -- "Nothing is too hard for you" (101)

Then Bell shifts to God's purpose and love by looking at these chapters.

Psalm 145 -- "is good to all; he has compassion on all he has made" (101)

Psalm 30 -- "lasts only a moment, but his favor lasts a lifetime" (101)

Psalm 145 -- "is gracious and compassionate, slow to anger and rich in love" (101)

Philippians 2 -- "it is God who works in you to will and to act in order to fulfill his good purpose" (101)

Luke 15 -- God never ever gives up until everything is found (101-102)

After sharing his understanding of these passages, Bell rhetorically asks,

Another thing one should do before forming conclusions from this chapter is look at the passage that drives it-- First Timothy 2:3-4. The critical aspect of this argument depends on the words "wants" or "desires" (from the NIV or ESV translation.) and 'all people.' 'Want' or 'desire' is translated from the Greek word thelō, which means, to choose or prefer, wish, will, desire, intend, to have, to be inclined to, to be disposed to, to purpose, to resolve to, to love, and Thayer even says it could be "to seize with the mind" or to "have in mind." Obviously in the English language, when we have a word with such a wide range of meaning, context is very important. This is true in the Greek too. (To get a good idea of this word, here are all the places thelō, or its negation appear in the New Testament: Matt 1:19; 2:18; 5:40, 42; 7:12; 8:2–3; 9:13; 11:14; 12:7, 38; 13:28; 14:5; 15:28, 32; 16:24–25; 17:4, 12; 18:23, 30; 19:17, 21; 20:14–15, 21, 26–27, 32; 21:29; 22:3; 23:4, 37; 26:15, 17, 39; 27:15, 17, 21, 34, 43; Mark 1:40–41; 3:13; 6:19, 22, 25–26, 48; 7:24; 8:34–35; 9:13, 30, 35; 10:35–36, 43–44, 51; 12:38; 14:7, 12, 36; 15:9, 12; Luke 1:62; 4:6; 5:12–13, 39; 6:31; 8:20; 9:23–24, 54; 10:24, 29; 12:49; 13:31, 34; 14:28; 15:28; 16:26; 18:4, 13, 41; 19:14, 27; 20:46; 22:9; 23:8, 20; John 1:43; 3:8; 5:6, 21, 35; 6:11, 21, 67; 7:1, 17, 44; 8:44; 9:27; 12:21; 15:7; 16:19; 17:24; 21:18, 22–23; Acts 2:12; 7:28, 39; 10:10; 14:13; 16:3; 17:18; 18:21; 19:33; 24:27; 25:9; 26:5; Rom 1:13; 7:15–16, 18–21; 9:16, 18, 22; 11:25; 13:3; 16:19; 1 Cor 4:19, 21; 7:7, 32, 36, 39; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:3; 12:1, 18; 14:5, 19, 35; 15:38; 16:7; 2 Cor 1:8; 5:4; 8:10–11; 11:12; 12:6, 20; Gal 1:7; 4:9, 17, 20–21; 5:17; 6:12–13; Phil 2:13; Col 1:27; 2:1, 18; 1 Th 2:18; 4:13; 2 Th 3:10; 1 Tim 1:7; 2:4; 5:11; 2 Tim 3:12; Philem 1:14; Heb 10:5, 8; 12:17; 13:18; James 2:20; 4:15; 1 Pet 3:10, 17; 2 Pet 3:5; 3 John 1:13; Rev 2:21; 11:5–6; 22:17.)

What does Paul mean in his letter to Timothy when he says God 'desires' or 'wants'? And what is meant by 'all people'? It seems this passage may have been written in the same light as John 3:16 and 2 Corinthians 5:14-15. How should we understand God's desires in light of John 6:40 which reads, "For this is the will of my Father, that everyone who looks on the Son and believes in him should have eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day" (ESV)? As the Timothy passage is examined, one must ask if 'wants' is the same as 'wills' or 'decrees.' Can God have a desire for his people that does not come to pass? Did God have a desire for Adam and Eve to avoid the forbidden fruit? I believe the answer is yes. And when man does not do what God wants or desires, who has failed, man or God? Does God desire that little Rwandan kids get their limbs cut off by their parents' enemies? Does God desire that women be raped? The answer is no! But according to Bell's argument, if God doesn't get what he desires, God has failed. The Bible teaches that man has failed and has acted against God's desires. The definition for this is sin.

Also, 'all people' might be in reference to every person throughout all of time, or it could be in reference to all kinds of people, every tribe, tongue, age, sex, and nation. Either way, it is reasonable that God would like to see everybody turn back to him and profess their submission and love for their Creator even though the sin nature, depravity, or even free will could keep some from doing so. In light of what the meta-narrative of the Bible teaches, it seems that salvation is universal in its availability, but this availability does not necessarily suggest that it is automatic or guaranteed that all will be saved.

Towards the end of the chapter, Bell sets up his safety net, first asking,

Personally, for a book "About heaven and hell, and the fate of every person who ever lived" I find Bell's attempt to provide answers a bit lacking. This answer says nothing about the fate of anybody and therefore suggests that Bell has failed to deal with the basic premise that his books claims to address. According to Bell, the fate of every person who ever lived is, 'I don't know. We can't know. Don't worry about it, but leave room for love,'

Can I have my money back?

Up next, "Love Wins by Rob Bell (Chapter 5)."

* I have no material connection to Rob Bell or his book, Love Wins.

At this point, I have two confessions. First, I put the book down after Chapter Three for a while. I was feeling frustrated that I set out on this journey through Bell's book. Second, I have now completed the book, having read the remaining chapters during a flight across the country. This is not to say that the review from this point forward will not capture my thoughts and impressions as I was reading each chapter. I've been taking notes and recording my thoughts in the margins and in the bizarre spaces between each paragraph that make the book seem as if were intended to be one long blog post rather than a bound book. I guess now I'm thankful for the abnormal formatting.

The title of Chapter Four asks, "Does God Get What God Wants?"

But first, Bell opens the chapter with jabs at doctrinal statements found on other church websites. It is clear that he is in disagreement with their approach of sharing their beliefs on what he feels should be a welcoming, seeker-friendly website. (Interestingly, while Bell defends his own ideas saying, "[Christian faith] is a deep, wide, diverse, stream that's been flowing for thousands of years, carrying a staggering variety of voices, perspectives, and experiences" (x-xi), he seems for forget to leave room for these other churches. Is the stream only so wide and so diverse that other churches are only accepted if their ideas are flowing the way Rob Bell wants? It does seem so.

Chapter Four is about universalism, and thus far, if any chapter has demonstrated that Bell has beliefs in the universalism camp, it's this one. (I realize that outside of the book, Bell has been declaring that he is not a universalist, but there are aspects of this chapter that would argue otherwise.) Here, Bell discusses universalism--that is, his views of universalism, specifically two views. The first is that heaven is "a universal hugfest where everybody eventually ends up around the heavenly campfire singing 'Kumbaya,' with Jesus playing guitar" (105). Through jabbing questions, he implies that this is incorrect and nobody would want this anyway. The second view is that a person has rejected God so much so that he or she is no longer human; thus all humans go to heaven but all non-humans do not. But this implies that there are people that are not human and that kind of implies an us verses them. Then he argues that these are long standing and traditional views starting with the early Christian church (107). But while Bell argues against these views (or I should say, he asks loaded questions of them), he conveniently never takes a position for himself. He doesn't ever seem to suggest a correct answer; he only questions the ideas for which which he doesn't care for or agree. And in the way he questions, he seems to takes a stand against these views, much like his approach to the other Christian's websites.

Back to the question of the chapter title: "Does God Get What God Wants?" The bulk of this chapter--and I might argue much of the books thus far--hinges on a verse in First Timothy 2. Bell quotes it as, "God wants all people to be saved and come to a knowledge of the truth" (97). The passage itself comes from First Timothy 2:3-4 and this translation looks very similar to the NIV version. The ESV translates the verses as, "This is good, and it is pleasing in the sight of God our Savior, who desires all people to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth" (1 Timothy 2:3-4, ESV). Bell's argument goes like this: If God wants something and doesn't get it, he's not powerful and therefore not a good God. However, Bell argues, God does indeed get everything he wants and therefore everybody WILL be saved and have a knowledge of the truth. . . eventually. And if Bell's way of thinking about this is not correct, according to his own argument, then God must be a failure.

To support his understanding of this specific Scripture, Bell looks at some other verses (citing only the chapters from where they come). First he looks at Isaiah 45, Malachi 2, Acts 17, and Romans 11, to argue "What we have in common--regardless of our tribe, language, customs, beliefs, or religion--outweighs our differences. This is why God wants 'all people to be saved'" (99). Then using other Scripture, Bell works to show his readers that the Bible says everybody will be saved. Many of the Scriptures are interpreted with questionable methods. Here's the list of Scriptures Bell uses to support his unrealistic view that everybody will be saved. I highly recommend you turn to each of these chapters and read them yourself, in their entirety.

Psalm 65 -- "all people will come" to God (99)

Ezekiel 36 -- "The nations will know that I am the Lord" (99)

Isaiah 52 -- "All the ends of the earth will see the salvation of our God" (99)

Zephaniah 3 -- "Then I will purify the lips of the peoples, that all of them may call on the name of the Lord and serve him shoulder to shoulder"

Philippians 2 -- "Every knee should bow . . . and every tongue acknowledge that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father." (99)

Psalm 22 -- "All the ends of the earth will remember and turn to the Lord, and all the families of the nations will bow down before him." (100)

Psalm 22 -- "All the rich of the earth will beast and worship; all who do down to the dust will kneel before him--" (100)

Shifting to the idea that God does not fail, Rob uses Psalm 22 to say, "So everybody who dies will kneel before God, and 'future generations will be told about the Lord. They will proclaim his righteousness, declaring to a people yet unborn: He has done it!'" (100). Following this passage, Bell again says that God does not fail and it is this idea that the prophets were affirming. They turned to this theme again and again (100). To support this claim, Bell turns to more chapters. Again, I suggest these chapters be read in their entirety.

Job 23 -- "Who can oppose God? He does whatever he pleases" (100)

Job 42 -- "I know that you can do all things; no purpose of yours can be thwarted" (100)

Isaiah 46 and 25 -- "Surely the arm of the Lord is not too short to save nor his ear too dull to hear?" (101)

Jeremiah 32 -- "Nothing is too hard for you" (101)

Then Bell shifts to God's purpose and love by looking at these chapters.

Psalm 145 -- "is good to all; he has compassion on all he has made" (101)

Psalm 30 -- "lasts only a moment, but his favor lasts a lifetime" (101)

Psalm 145 -- "is gracious and compassionate, slow to anger and rich in love" (101)

Philippians 2 -- "it is God who works in you to will and to act in order to fulfill his good purpose" (101)

Luke 15 -- God never ever gives up until everything is found (101-102)

After sharing his understanding of these passages, Bell rhetorically asks,

"Will 'all the ends of the earth' come, as God has decided, or will only some? Will all feast as it's promised in Psalm 22, or only a few? Will everybody be given a new heart, or only a limited number of people? Will God, in the end, settle, saying: 'Well, I tried, I gave it my best shot, and sometimes you just have to be okay with failure'? Will God shrug God-sized shoulders and say, 'You can't always get what you want?'" (103).These questions seem to lead to a specific answer, and that answer looks a lot like universalism. But before we come to a definitive answer for any of these questions, it might be helpful to look at some other Scriptures. While there is intense debate on both sides of this argument (as well as the one regarding how much free will man may have) it may be valuable to at at least look at these chapters and verses and ask how they compare to the presentation Bell has provided. I realize that different interpretations will lead to different answers (a strong reason for good exegesis and hermeneutical practices). If all are saved in the end, why are these Scriptures in the Bible? Look at Daniel 12:2; Matthew 18:8, 25:42-46; John 5:29; Romans 14:12; Ephesians 2:8-9, 2 Thessalonians 1:8-9; Jude 7; and Revelation 14:11. Also, I realize that a universalist may argue that even though everybody ends up in heaven in the end, the reason for accepting Jesus now is to receive the blessing that he provides now. But still, is that the only reason then for Matthew 28:18-20?

Another thing one should do before forming conclusions from this chapter is look at the passage that drives it-- First Timothy 2:3-4. The critical aspect of this argument depends on the words "wants" or "desires" (from the NIV or ESV translation.) and 'all people.' 'Want' or 'desire' is translated from the Greek word thelō, which means, to choose or prefer, wish, will, desire, intend, to have, to be inclined to, to be disposed to, to purpose, to resolve to, to love, and Thayer even says it could be "to seize with the mind" or to "have in mind." Obviously in the English language, when we have a word with such a wide range of meaning, context is very important. This is true in the Greek too. (To get a good idea of this word, here are all the places thelō, or its negation appear in the New Testament: Matt 1:19; 2:18; 5:40, 42; 7:12; 8:2–3; 9:13; 11:14; 12:7, 38; 13:28; 14:5; 15:28, 32; 16:24–25; 17:4, 12; 18:23, 30; 19:17, 21; 20:14–15, 21, 26–27, 32; 21:29; 22:3; 23:4, 37; 26:15, 17, 39; 27:15, 17, 21, 34, 43; Mark 1:40–41; 3:13; 6:19, 22, 25–26, 48; 7:24; 8:34–35; 9:13, 30, 35; 10:35–36, 43–44, 51; 12:38; 14:7, 12, 36; 15:9, 12; Luke 1:62; 4:6; 5:12–13, 39; 6:31; 8:20; 9:23–24, 54; 10:24, 29; 12:49; 13:31, 34; 14:28; 15:28; 16:26; 18:4, 13, 41; 19:14, 27; 20:46; 22:9; 23:8, 20; John 1:43; 3:8; 5:6, 21, 35; 6:11, 21, 67; 7:1, 17, 44; 8:44; 9:27; 12:21; 15:7; 16:19; 17:24; 21:18, 22–23; Acts 2:12; 7:28, 39; 10:10; 14:13; 16:3; 17:18; 18:21; 19:33; 24:27; 25:9; 26:5; Rom 1:13; 7:15–16, 18–21; 9:16, 18, 22; 11:25; 13:3; 16:19; 1 Cor 4:19, 21; 7:7, 32, 36, 39; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:3; 12:1, 18; 14:5, 19, 35; 15:38; 16:7; 2 Cor 1:8; 5:4; 8:10–11; 11:12; 12:6, 20; Gal 1:7; 4:9, 17, 20–21; 5:17; 6:12–13; Phil 2:13; Col 1:27; 2:1, 18; 1 Th 2:18; 4:13; 2 Th 3:10; 1 Tim 1:7; 2:4; 5:11; 2 Tim 3:12; Philem 1:14; Heb 10:5, 8; 12:17; 13:18; James 2:20; 4:15; 1 Pet 3:10, 17; 2 Pet 3:5; 3 John 1:13; Rev 2:21; 11:5–6; 22:17.)

What does Paul mean in his letter to Timothy when he says God 'desires' or 'wants'? And what is meant by 'all people'? It seems this passage may have been written in the same light as John 3:16 and 2 Corinthians 5:14-15. How should we understand God's desires in light of John 6:40 which reads, "For this is the will of my Father, that everyone who looks on the Son and believes in him should have eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day" (ESV)? As the Timothy passage is examined, one must ask if 'wants' is the same as 'wills' or 'decrees.' Can God have a desire for his people that does not come to pass? Did God have a desire for Adam and Eve to avoid the forbidden fruit? I believe the answer is yes. And when man does not do what God wants or desires, who has failed, man or God? Does God desire that little Rwandan kids get their limbs cut off by their parents' enemies? Does God desire that women be raped? The answer is no! But according to Bell's argument, if God doesn't get what he desires, God has failed. The Bible teaches that man has failed and has acted against God's desires. The definition for this is sin.

Also, 'all people' might be in reference to every person throughout all of time, or it could be in reference to all kinds of people, every tribe, tongue, age, sex, and nation. Either way, it is reasonable that God would like to see everybody turn back to him and profess their submission and love for their Creator even though the sin nature, depravity, or even free will could keep some from doing so. In light of what the meta-narrative of the Bible teaches, it seems that salvation is universal in its availability, but this availability does not necessarily suggest that it is automatic or guaranteed that all will be saved.

Towards the end of the chapter, Bell sets up his safety net, first asking,

"[W]e read in these last chapters of Revelation that the gates of that city in the new world will 'never shut.' That's a small detail, and it's important we don't get too hung up on the details and specific images because it's possible to treat something so literally that it becomes less true in the process. But gates, gates are for keeping people in and keeping people out. If the gates are never shut, then people are free to come and go.Immediately following this he asks, "Will everybody be saved or will some perish apart from God forever because of their choices?" (115). Then in a rare moment that exists hardly anywhere else in the Love Wins, Rob Bell tires to answer his own questions. He writes, "Those are questions, or more accurately, those are tensions we are free to leave fully intact. We don't need to resolve them or answer them because we can't, and so we simply respect them, creating space for the freedom love requires" (115). Um, Mr. Bell, didn't you just argue that God does in fact get what God wants? And according to the way you understand First Timothy 2:3-4, doesn't God want everybody to be saved? So based on the argument you've constructed, won't everybody be saved in the end, eventually? Everybody will be in the new creation as God wills; isn't that what you argued? Doesn't it seem more like your universalist answer is, 'Yes, everybody will be saved, nobody will perish apart from God forever because of their choices'? The answer Bell provides for his own question seems to run counter to the entire chapter.

Can God bring proper, lasting justice, banishing certain actions--and the people who do them--from the new creation while at the same time allowing and waiting and hoping for the possibility of the reconciliation of those very same people? Keeping the gates, in essence, open? Will everyone eventually be reconciled to God or will there be those who cling to their version of their story, insisting on their right to be their own little god ruling their own little miserable kingdom?" (115).

Personally, for a book "About heaven and hell, and the fate of every person who ever lived" I find Bell's attempt to provide answers a bit lacking. This answer says nothing about the fate of anybody and therefore suggests that Bell has failed to deal with the basic premise that his books claims to address. According to Bell, the fate of every person who ever lived is, 'I don't know. We can't know. Don't worry about it, but leave room for love,'

Can I have my money back?

Up next, "Love Wins by Rob Bell (Chapter 5)."

* I have no material connection to Rob Bell or his book, Love Wins.